::: center

Collaborating for Comprehensivity

:::

::: titlepage

Collaborating for Comprehensivity

CJ Fearnley

Licensed under Creative Common Licence CC BY 4.0 |

ISBN: 978-000000000-0

ISBN-10: 0

Updated: 2024-12-07

:::

Note: This material in this book reproduces essays of CJ Fearnley published at https://www.cjfearnley.com/CfC/. The introduction appears at this url. The 26 Resource Center essays are at https://www.cjfearnley.com/CfC/resource-center/.

¶ Introduction: What is Comprehensivity? How it works? Why it works?

¶ Introducing an idea to better understand our worlds and their peoples

Our civilization is so complex that there is a widespread feeling of fragmentation, disorderliness, and incomprehensibility. How can ordinary citizens like you and me redress these major shortcomings in our social worlds?

We think that, despite the apparent difficulties, it is possible for groups of people working collaboratively to significantly improve their understanding of our worlds in all their exquisite complexity.

We think the ongoing stability and thriving of our civilization depends on such a comprehensively informed citizenry.

Buckminster Fuller argued that comprehensivity, an innate-in-children but largely absent-in-schooling proclivity to comprehend the world and each other broadly and deeply, is essential for the general adaptability of humanity. We aim to develop this germ of an idea into a system for improving humanity s comprehensivity.

We call for an ongoing initiative with groups of citizens working together to explore our worlds and its peoples.

We aim to foster a comprehensivity that understands enough about enough of the vital aspects of how our worlds work and change to make sense of it all and of each other.

We aim to establish the vital importance of Buckys guiding epistemic virtue of comprehensivity, striving toward “the adequately macro-comprehensive and micro-incisive”.

We aim to foster collaborations where participants engage in dynamic explorations where they whet each others ideas into sharper more incisive understandings to better learn how it all works.

We aim to build a new tradition of inquiry and action focused on our comprehensivity.

We aim to unify our worlds both conceptually and physically.

Since dynamic, creative experimentation is the wisest way to start any new initiative, this site is just a starting point, some guideposts for the beginning. Please carefully consider this draft schema or outline for creating the new tradition of comprehensive practice that we aspire to bring forth. After reading about the idea and our nascent effort to implement it, let us know how we can improve it and how you can help us build it. Your ongoing input will be essential for it to succeed!

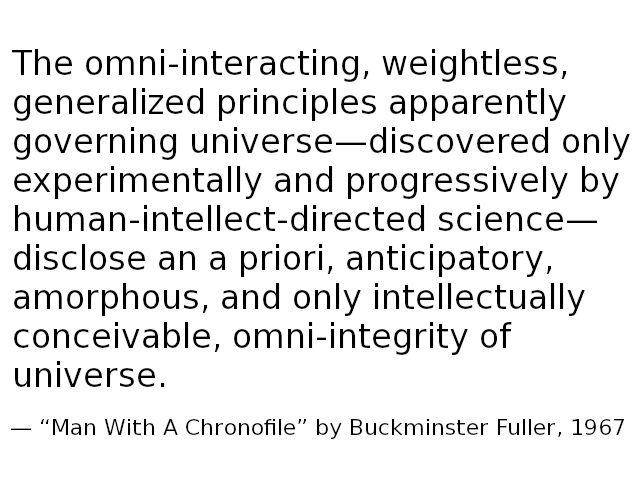

[Humanity] is being forced to reestablish, employ, and enjoy [their] innate “comprehensivity”.[1]

¶ The Vision

Become a Comprehensivist …Become a better, more aware, more informed citizen

Learn how the world works …Examine how change is created … Learn how other people think

Explore diverse subjects broadly and deeply …Learn what the world means and what possibilities it holds

Understand more of the many traditions of inquiry and action that drive our civilization and our lives

Organize and Participate in Explorations to comprehend how the world works and how it changes

Become a better, more sensitive listener

Become a better, more articulate speaker

Practice the art of being a trimtab (small actions that effect big results)

Together we can gradually become more and more effective doers and thinkers in addressing the topics that matter in our lives and in the world

Engage to more incisively comprehend the whole Universe together!

¶ The Benefits

-

To better understand each other in a world of silos and tribes

-

To better navigate our lives in a complex global civilization

-

To better form integrated multi-perspectival views of our worlds

-

To better team with others to achieve bigger objectives

-

To better imagine, assess, and communicate ideas and actions that may improve the operation and regenerativity of our global civilization

-

To become a social trimtab, that is, to better serve, coordinate, and guide associates, colleagues, and fellow-citizens as well as organizations, companies, and governments including our politicians

-

To improve our collective intelligence to make humanity more robustly adaptable to any and all possible futures

-

To provide a forum for the deliberation of the vital issues of our times so we can more effectively inform the governance systems of our civilization

-

To help realize, on an ongoing basis, Buckminster Fuller s great ethical aspiration “to make the world work for 100 percent of humanity in the shortest possible time through spontaneous cooperation without ecological damage or disadvantage to anyone”

-

To unify the world

¶ Collaborating Involves Group Explorations

¶ What is Comprehensivity?

-

Comprehensivity is our ability to comprehend our worlds broadly and deeply.

-

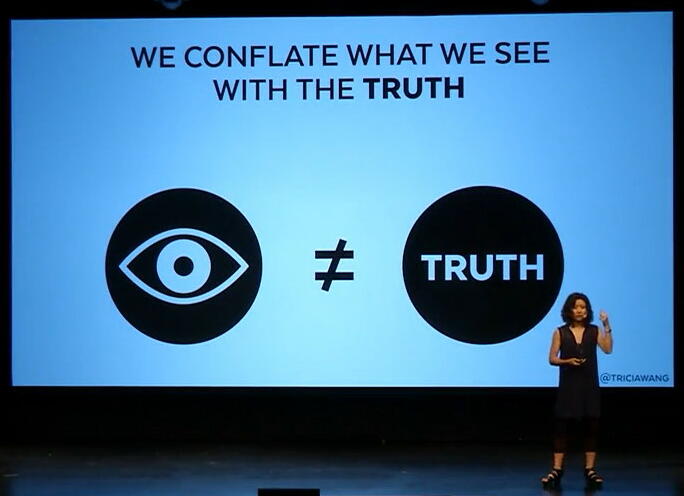

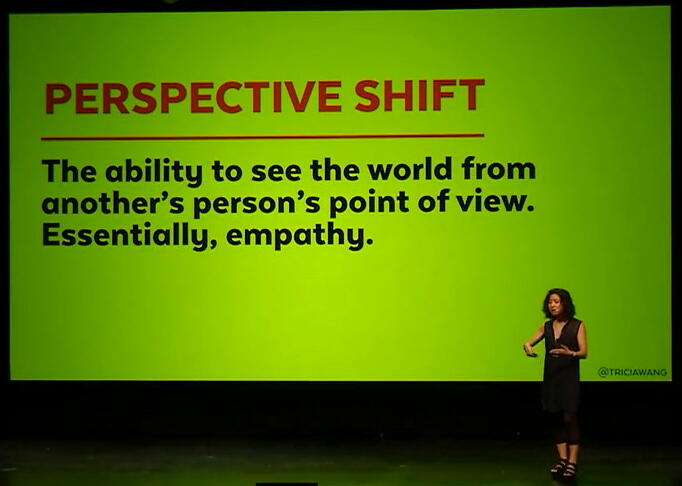

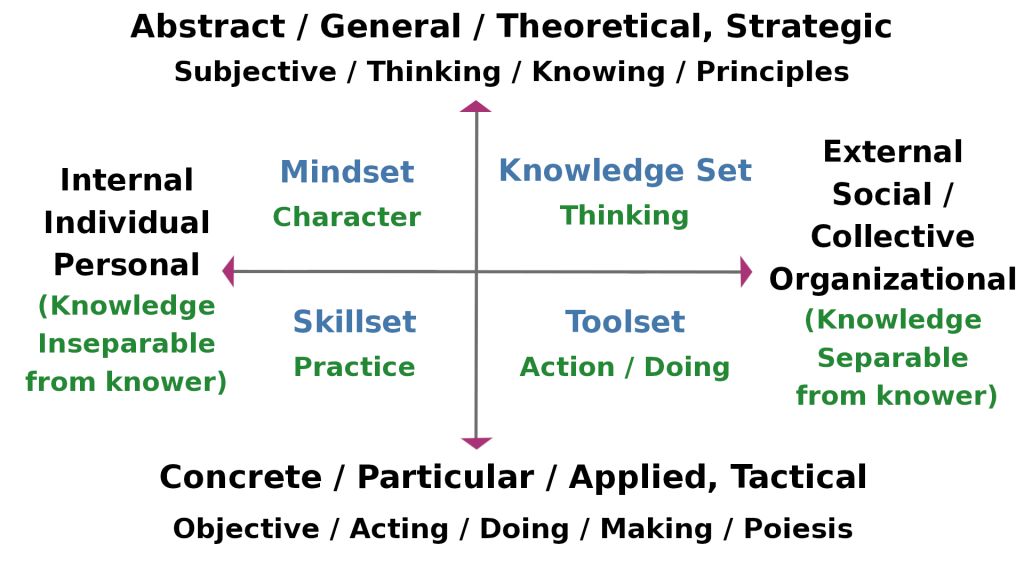

It is a facility in questioning, conceptualizing, interpreting, and acting to build a multi-perspectival yet integrated understanding of the world, how it works, and how it changes.

-

It is the quality of our lives that shapes all we have learned in breadth for context and all we have learned in depth for clarity to form, as Buckminster Fuller put it, “adequately macro-comprehensive and micro-incisive´´ considerations to better engage our worlds and its peoples with understanding and effectiveness.

-

It implies developing a large set of subjects about which one can effectively inquire, contextualize, interpret & assess, and creatively re-imagine and re-combine for meaningful insights and the forging of new possibilities.

-

It entails developing a faculty for helping self and others build a broad range of interests and concerns, comprehensive knowledge, and skills, that is, a faculty for comprehensivity awareness and competency.

-

It involves recognizing its inherent pathologies including analysis paralysis (an endless accumulation of information), value paralysis (an unrestrained accommodation of everyones values), and the paralysis of wholism (an unlimited expansion of the whole). So it requires cultivating judgment to stay incisively relevant.

Since it is impossible for any one person to understand all of humanity s accumulated knowing and doing, comprehensive learning may seem unachievable. The idea is that our individual and collective effectiveness in understanding the vital issues of our times will be improved through the dynamics of groups of people effectively exploring many different topics as broadly and deeply as possible over an extended period of time. Guided by the intention to develop an incisively integrated comprehension of our worlds and how they change, participants will inform and gradually hone their judgment both in the areas specifically explored as well as in gradually acquiring general adaptability. Bit by bit, they will become better prepared to ask more incisive questions and imagine more effective actions on subjects for which they have little prior knowledge or awareness. Their insights, new possibilities, and actions will percolate through society enhancing the collective intelligence and adaptability of our civilization as a whole.

Collaborating for comprehensivity welcomes participation from anyone willing to suspend their own certainties to conscientiously explore sensitively, boldly, and collaboratively. Sessions should involve no prerequisite knowledge, beliefs, metaphysical assumptions, or values beyond the communicating systems used to organize and conduct events. We recommend a crowdsourcing model where participants explore their own topics in their own order curated and explored by the participants themselves. At group events, they exchange experiences, interpretations, beliefs, feelings, values, thoughts, models, apprehensions, understandings, and ways of seeing (perceiving), thinking, and doing. That is, we envision building a new tradition that focuses on listening, sharing, and exploration and which accommodates and includes all backgrounds, beliefs, and cultural traditions.

Does the idea interest you?

What do you like about it? Do you have any concerns?

¶ A New Tradition of Inquiry and Action

Collaborating for comprehensivity aspires to develop, democratize, and institutionalize a new tradition of inquiry and action inspired by the great polymaths of history like Aristotle, Archimedes, Zhang Heng, Hypatia, Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen), Ibn Sina (Avicenna), Shen Kuo, Omar Khayyám, Acharya Hemachandra, Hildegard of Bingen, Albertus Magnus, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, Leonardo, Cornelius Agrippa, Athanasius Kircher, Christina Queen of Sweden, Ben Franklin, Maria Gaetana Agnesi, Goethe, William Whewell, Buckminster Fuller, John von Neumann, Jacob Bronowski, Mortimer J. Adler, and Dorothy Dunnett. Although anyone can become a comprehensivist by putting into practice studying, thinking, and acting broadly, currently society produces too few comprehensivists, too few who are able to connect humanity s great traditions and its peoples. Our effort aspires to engage anyone who is interested to participate in and/or organize collaborations with a minimum of background, training, and effort.

There are many traditions of inquiry and action that purport to provide initiates with the means to grasp anything (or even everything) including our many spiritual, mystical, and mythological traditions, science and technology, Renaissance humanism, pansophism, the liberal arts, transdisciplinarity, mathesis universalis, universology, consilience, wholism, integral theory, world-systems theory, cultural studies, semiotics, complexity, systemics, cybernetics, and synergetics. While these organizing systems are important cultural resources and should be better understood, none is universally accepted, their assumptions are often controversial, and most involve first learning particular ways of seeing and sophisticated practices of inquiry and action. Instead, collaborating for comprehensivity aims to accommodate the broadest range of people and their traditions in a quest, an exploration, whose direction is clear (toward the broad in scope AND the deeply incisive: toward comprehensivity) but whose destination is unspecified and open-ended.

In “Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth”, Buckminster Fuller wrote, “We have not been seeing our Spaceship Earth as an integrally-designed machine which to be persistently successful must be comprehended and serviced in total”. So comprehensive practice is needed to effectively operate our spaceship effectively. It aspires to a planetary or cosmic perspective in both our conceptuality and in our practice.

¶ An idea to unify the world

In “Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth”, Buckminster Fuller (“Bucky”) called for an “uncompromised, metaphysical initiative of unbiased integrity [to] unify the world”.[2] Could attending to our comprehensivity help unify the world?

An inspiring model for unification and comprehensivity can be found in the scientific theory of gravity developed by Newton, Einstein, and others. Evidently, every massive particle in the entire physical Universe attracts every other according to an exact mathematical formulation. This expression of universal physical love belies the boundaries and fragmentations of our present-day tribes and silos. It could be that we can similarly develop schemas or models that accommodate every idea and every person in a meticulously comprehensive gestalt despite how daunting it may at first appear?

In speaking about Dantes 700-year-old epic poem “La Commedia”, Giuseppe Mazzotta said, “the presence of viewpoints, various viewpoints, which one somehow manages to control, or know, all viewpoints. …Perspective means that…the perception of reality changes according to the position we occupy…. Dante uses this perspectivism [which] really means a way of assembling various points of view.” Likewise, our comprehensivity assembles and integrates a broadly informed multi-perspectival view of our worlds. Collaborating with many people of different backgrounds, we can facilitate acquiring such a perspectivism. So our initiative engages groups of people to collaborate to gradually realize a broader and deeper and more integrated conception of our worlds.

A collaborative effort to facilitate our comprehensivity inspired by the science of gravity and informed by perspectivism could unify the world. Not only would a comprehensively informed conception of the world be more unified than our fragmented ones, but a side effect of identifying and sharing comprehensivist considerations, insights, possibilities, and actions would tend to help everyone better understand each other and better coordinate their actions which would tend to unify the world. These effects might make our civilization more robustly adaptable to any and all possible futures.

Collaborating for comprehensivity is a nascent initiative to engage groups of citizens in diverse explorations to develop comprehensive comprehensions to unify our worlds conceptually and physically.

¶ How it works

Our nascent tradition to cultivate our comprehensivity is still inchoate. There are no textbooks. We cannot be sure which of our ideas will work and which may need to be discarded. We welcome your experiments to test our ideas and to try out your ideas so that over time we may learn the best ways to foster our comprehensivity.

We have organized more than 300 events that have served to prototype the idea. Based on that experience, we offer these recommendations and suggestions for how collaborative groups might be structured so that we might build an effective community of practice:

-

Groups would ideally meet face-to-face on a recurring basis for a series of conversations (generally exploratory dialogues, but other activities may sometimes be used) to explore a wide variety of topics. Explorations will be broader and richer if participants have diverse backgrounds, knowledge, and skills. So diversifying your group will be well worth the effort.

-

Each exploration must ensure the psychological safety of participants so respectful but penetrating probing of strong differences can be effectively engaged and integrated into meaningful outcomes.

-

Ideally, all participants will contribute their thoughts and feelings about the subject. Event facilitators ought to start each meeting by inviting each participant to introduce themselves and to comment on the topic to get everyone comfortable with sharing their ideas and to provide stepping stones for exploration.

-

Topics ought to be curated so that with a minimum of preparation, participants with no prior awareness of the subject can effectively explore its nuances. Requiring some preparation will produce richer events. Some events should be based on books, videos, or other resources that require more preparation. Please experiment. If too many events involve too much preparation, participants may not feel prepared and may not contribute to the conversation. Good condensed summaries can make advanced ideas accessible for everyone. Topic curation involves preparing participants to explore a subject deeply even when they have no background.

-

Our focus on exploration requires that all participants must suspend their certainties so they can fully engage and examine each other s ideas. Participants are encouraged to share their relevant ideas and even their judgments, but certainty derails exploration. Asking someone who is a bit too certain to explain why they hold their beliefs and then asking the rest of the group to share their beliefs and their justifications for them will often facilitate a transition to a deeper exploration. The group must strive get beyond the shallow batting around of opinions and beliefs that we typically witness on TV. By exploring the range of opinion in the group with a suspension of certainty, everyone can feel heard and most people will naturally transition from partisan “believers” to explorers who listen to and collaboratively build on each othersideas.

-

Each participant ought to organize topics for the group to explore. This is important: only by assessing what is lacking in your own or your group’s comprehensivity will you be able to steer you and your group to more effective considerations. Groups should compassionately mentor any member who struggles in organizing their topics.

-

All subjects ought to be “on the table” for exploration. Even seemingly parochial topics can engage our comprehensivity when we recognize that everything is interrelated (witness the physics of gravity!) and we see the challenge of our resistance to a topic as an opportunity to work through our blocks to a more encompassing comprehensivity.

-

Groups may benefit from exploring meta-issues such as the importance of listening, voicing, respect, suspension of certainty, and other skills for fostering more effective dialogue and exploration.

-

If participants boldly explore the edges of their knowledge and their differences, the meetings will end without a conclusion and with everyone in a state of cognitive dissonance. That is to be expected: it indicates a successful session! The discomfort of cognitive dissonance may be reduced by ending sessions by asking participants about what they learned, what their takeaways from the dialogue were, and whether they glimpsed further into comprehensivist seeing, thinking, or practice. Participants will then be able to build on these insights later.

-

Given how complex our worlds are, it can be expected that it will take years to develop a confident comprehensivity. Participants and groups should be patient with their progress yet not shy away from challenging themselves to consider many unfamiliar perspectives. Progress may require confronting and accommodating your biggest intellectual weaknesses, fears, and aversions!

Every group will be different. Every topic will be different. Organizers will try experiments. Some wont work. The basic outline above should provide a rough and ready guide for most groups. If you learn something from your practice, please share it with us so we can all learn more quickly.

Are you ready to collaborate for comprehensivity? Why? Why not?

What do you think of our approach to fostering comprehensivity?

¶ Why It Works

Our approach to collaborating for comprehensivity aligns the interests of citizen-stakeholders through a mutual commitment to understanding each other and how our worlds work and change. This motivation is explained in the Buckminster Fuller quote: “One of humanitys prime drives is to understand and be understood”. Furthermore, dynamic, interactive dialogues where each participant is engaged to explore assumptions, to listen sensitively, to speak and be heard, to build ever broader and deeper meanings, and to identify new possibilities in subjects that matter can be thoroughly engaging.

One of our key ideas builds on Buckminster Fullers idea of a trimtab:

Something hit me very hard once, thinking about what one little man could do. Think of the Queen Marythe whole ship goes by and then comes the rudder. And theres a tiny thing at the edge of the rudder called a trimtab. Its a miniature rudder. Just moving the little trim tab builds a low pressure that pulls the rudder around. Takes almost no effort at all. So I said that the little individual can be a trimtab. Society thinks it s going right by you, that its left you altogether. But if youre doing dynamic things mentally, the fact is that you can just put your foot out like that and the whole big ship of state is going to go. So I said, call me Trimtab.[3]

Buckminster Fuller (“Bucky”)

Participants are trimtabs helping each other get leverage on their mutual aim to enhance their comprehensivity. That incentivizes contributions to broaden and deepen each exploration. Over time, participants ought to diagnose their own and their group s strengths, weaknesses, possibilities, and concerns for building a more meticulous, comprehensive, and integrated set of models of our worlds. Such navigational assessments will indicate new directions to explore for honing their sense of the world. These group trimtab effects align participants, group, and purpose.

At the societal level, each session focuses on aspects of our civilization s vital traditions and issues. These subjects are trimtabs to consider new perspectives and their stakeholder concerns. The insights from many such meetings from many allied groups will percolate through society. If such broadly informed comprehensions strengthen our collective intelligence, they would improve our adaptability and improve the governance of our civilization. Such ideas may help identify and align our interdependent interests producing a more robust, regenerative, and thriving society. These combined societal trimtab effects may even help achieve the ambition of Buckminster Fuller “to make the world work for 100 percent of humanity in the shortest possible time through spontaneous cooperation without ecological damage or disadvantage to anyone”.

Such an initiative to engage citizen-explorers in collaborating for comprehensivitycould help unify our worlds physically as well as conceptually.

¶ Collaborating for Comprehensivity Integrates People, Ideas, and Action

¶ How To Get Started

Right now, Comprehensivist Wednesdays is the only group experimenting with the idea of collaborating for comprehensivity anywhere in the world. Unless its format and time work for you, you will need to organize your own group. Since no one is able to organize groups on their own, group organizers will need to find others to help. They will need to find other participants at least, but aides, assistants, partners, and co-organizers would make the workload lighter and more effective. Who can help you get started?

The first step is to commit to help organize a collaborative group. Then you can work toward a first session. Spend some time considering: How do you want your group to work? Write out your ideas and your story as youll need them for recruiting participants and for facilitating sessions.

Next, prioritize first things first: choosing a venue, a topic for the first meeting, announcing the first event, how to start the meeting, handling lulls in the conversation, handling conflicting views and personalities, and ending the event. What contingencies can you anticipate and how would you handle them?

Getting people to your event will be challenging. A marketing effort will be required. Since large groups are more difficult to organize, starting with a small group of maybe 10 or 12 (or even 5) people will be easier. Meetup.com can bring one or two new people to your events, but their service is very expensive. Facebook and Eventbrite offer some free event organizing services. If you get creative, you may be able to get going with minimal or negligible expenses.

What is your draft plan to get started? What kind of help do you need to get started?

¶ Spontaneous Organizing

We would like to see this initiative take off as a social contagion where groups spontaneously form all around the world. We are working to imagine what kind of infrastructure would best support that result. Let us know if you have any ideas.

You are welcome to just jump in, start organizing a group, and share your results with us.

To help folks get started, we have a Resource Center with topical essays that we have used to organize explorations. You can either use them directly or use them as inspiration for forming your own topics and curricula for your initiative.

¶ Note on the Accessible Design of Our Resources

These ideas and tools are compiled to support initiatives for collaborative development of our comprehensivity, our inclination for comprehensive inquiry and action to better understand and participate in the world.

Our aspiration to be comprehensive means that as we add more and more resources, they tend to iterate more and more deeply into more and more traditions of comprehensive thinking. We aspire to make each of these resources accessible to all participants without prerequisites, without dependencies on other resources. Since the comprehensive approach aspires to integrating and accommodating other subjects some of which are also covered by other resources, there will frequently be overlap and there will sometimes be contradictions among our resources.

To eliminate the need to read prerequisites, each summarizes any ideas that were developed in other resources. Generally, there will be links to related resources so that interested readers can dig deeper. Readers should be able to read each resource on its own for an adequate first-cut exploration. Indeed, such cross-references might best be deferred on a first reading.

In brief, each resource is designed to be accessible on its own.

Some resources highlight a book, essay, video, or other material as the main focus for that resource. In these cases, it is generally recommended that participants read the book, essay, or video first. However, even here we have attempted to summarize the highlighted material so that each resource can be read and understood on its own, but some nuanced allusions to the referenced material may be lost if the highlighted material is not reviewed first.

¶ Humanity’s Great Traditions of Inquiry and Action

18 July 2020 in Resource Center.

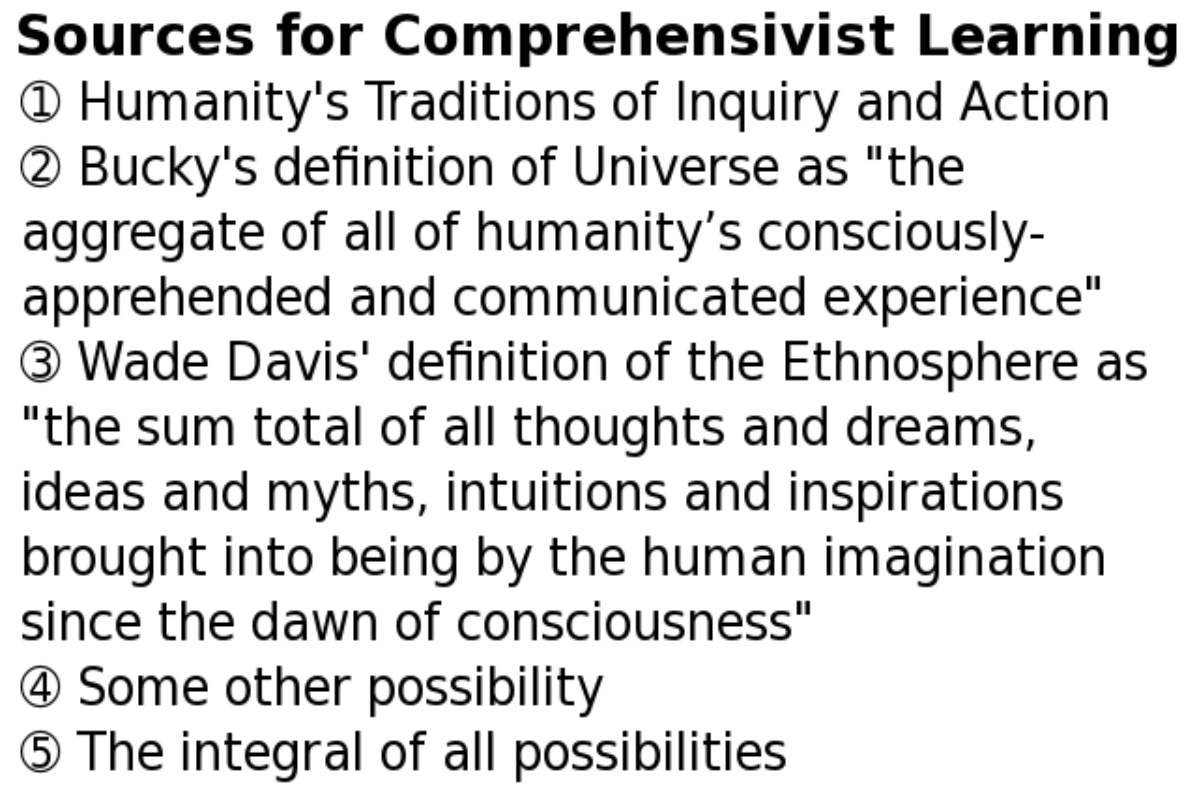

In order to undertake the project of becoming a comprehensivist to come to understand our worlds more and more broadly and deeply we need to provision a toolkit for the task. What are all the possible approaches that we might mobilize in our quest to make sense of it all and of each other?

The Design Way[4] by Harold G. Nelson and Erik Stolterman argues that design, not any of the arts or sciences, was humanity’s first “tradition of inquiry and action´´. The “Great Books” and “Great Ideas” collections of Mortimer J. Adler and others, inspired us to prefix the word “great” in front of the phrase from The Design Way. We now reformulate our initial question as What are the Great Traditions of Inquiry and Action that humanity has accumulated through the ages? Will this suffice to delimit the range of possible approaches which a comprehensivist might assay?

First, let’s pause to ask: Is it necessary and/or sufficient to encompass all humanity’s traditions with the metaphysics of inquiry and action? I am not at all sure, but since we need some organizing principle, as with all proposed and allegedly “obvious” first principles, we might just accept “inquiry and action” as a good enough working hypothesis of the nature of all humanity’s traditions without too much thought and boldly adopt it.

¶ Cataloguing Humanity’s Great Traditions of Inquiry and Action

We might attempt to circumscribe the comprehensivist’s purview with a survey of university courses. Certainly, in modern civilization, these courses catalogue some of the most important traditions in support of civilization’s dynamic functioning. However, the courses that make it into the repositories of free on-line course platforms or into the offerings of any given college or university are limited to those deemed suitable to “academic standards” and market demand. That limits the scope of comprehensiveness that we seek.

The comprehensivist might also assay the vocational training of technicians and artisans, books, journals, magazines, newspapers, articles, essays, reports, documentaries, films, video shorts, museums, libraries, artifacts of industrial and craft traditions, and many other resources. All of these can be passed on from person to person and ideally from generation to generation and so represent a tradition of inquiry and action. They are all excellent resources, but the comprehensivist seeks the broadest possible ken.

How can we encompass the broadest horizon possible? Consider this quote from W. E. H. Stanner’s essay “The Dreaming” about the philosophy of Australian Aborigines:

“It took well over half a century for Europeans to realize that, behind the outward show, was an inward structure of surprising complexity. It was a century before any real understanding of this structure developed. In one tribe with which I am familiar, a very representative tribe, there are about 100 ‘invisible’ divisions which have to be analysed before one can claim even a serviceable understanding of the tribe’s organization. The structure is much more complex than that of an Australian village of the same size. The complexity is in the most striking contrast with the comparative simplicity which rules in the two other departments of aboriginal lifethe material culture, on the one hand, and the ideational or metaphysical culture on the other.”[5]

From this report, we may infer that we must not only survey humanity’s various traditions of ideational culture (our ideas), and also humanity’s rich and varied material cultures including the arts and technology, but also the social structures which, at least in Stanner’s assessment of Aborigines, may sometimes be more intricate than we, who live in villages and cities with our extensive divisions of labor, may be conscious of or able to appreciate.

We have now identified three macro-comprehensive categories of traditions of inquiry and action that the comprehensivist should strive to survey and assay: traditions of ideas, material culture, and social structures.

Is the list complete? No, we have omitted the micro unit of human inquiry and action: the experience. Does each packaging of our lives into an experience comprise a tradition of inquiry and action? With the possible exception of the ineffable, experiences are communicable bundles of events and/or happenings, which seems to me sufficient to qualify as a tradition.

The packaging of an experience necessarily involves storytelling. So a story is more or less equivalent to the more grounded experience.

Would you admit any identified experience or story from any of Earth’s billions as a great tradition of inquiry and action which the comprehensivist may use for building their understanding of our worlds and its peoples?

I submit that this list of humanity’s traditions of inquiry and action is comprehensive: ideas, material culture, social structures, and experiences. What do you think of this categorization? Is this the ken of the comprehensivist?

Whenever we organize a categorization, we should think about Robert Sapolsky’s list of the dangers of categorical thinking: 1) we can miss the big picture by focusing on boundaries, 2) we tend to underestimate differences when two cases happen to fall in the same category, 3) we tend to overestimate differences when cases happen to fall on opposite sides of a boundary.

Sapolsky’s first concern leads us to wonder: What synergies of the whole might this categorization of humanity’s great traditions of inquiry and action obscure from us? Ought the comprehensivist always keep in mind the wholistic integral of all humanity’s traditions to keep fluid our perspective for any given particular exploration? I should think so. What do you think?

Sapolsky’s second two concerns lead us to ask: Are there items that would challenge the value of our distinctions? Certainly, for example, is music a tradition of material culture (instruments), of social structure (bands and acts), of experience (the music video), and of ideas (music theory)? All our distinctions become blurry when we analyze them too pedantically. Nonetheless, they are essential tools upon which we scope and structure our explorations.

How would you survey the inventory of approaches or traditions that we might mobilize in our quest to comprehensively comprehend our worlds and its peoples?

¶ Exploring Humanity’s Great Traditions

The total inventory of humanity’s great traditions of ideas, material culture, social structures, and experiences are too vast for any one person to explore systematically. Little, finite humans need some way to guide our efforts finding resources in this great unmappable repository to build our multi-perspectival yet integrated understandings of the world, how it works, and how it changes. How might we begin, given humanity’s abounding and sublime cultural heritage?

Some comprehensivists might limit themselves to assaying those traditions that purport to provide initiates with the means to grasp anything (or even everything). These are the great traditions of universalism. They include our many spiritual, mystical, and mythological traditions, science and technology, Renaissance humanism, the liberal arts, transdisciplinarity, universology, consilience, wholism, integral theory, world-systems theory, cultural studies, semiotics, complexity, systemics, cybernetics, and synergetics.

Should the comprehensivist focus on one or more universalist approaches to understanding the world? A big danger with these traditions is that they may prematurely fix our minds on one way of understanding precluding others. Since none of them is universally accepted, their assumptions can be controversial, and may involve extensive effort to learn, it may be better to dabble in them rather than focus too much on any one of them. Over time, we can iterate more and more into each without losing sight of the full inventory of the great traditions.

The universalist traditions have much to offer. I have spent much of my life exploring synergetics, science and technology, and the liberal arts. And I have made limited forays into wholism, cultural studies, complexity, systemics, cybernetics, semiotics, and integral theory. There should be no shame in focusing on any one of them, but the comprehensivist ought to keep in mind that other resources are available and may sometimes be more incisive than one’s favorite tradition.

How should an aspiring comprehensivist decide which tradition of inquiry and action to explore next?

I would recommend five considerations. First, if you have a life mission or objective, then from the full scope offered by the great traditions begin an exploration to see which might best contribute to your current situation.

Second, if you have a current project or interest, explore it thoroughly. Follow your interests and your desires. The book The Design Way asserts, “Desire is the destabilizing trigger for transformational change”. Comprehensivism is built incrementally: each project or interest that is comprehensively explored provides a stepping stone for an ever-broadening comprehensivism, no matter how parochial it may seem in isolation.

Third, try something that is way outside your comfort zone. As a math/science/philosophy guy, one of the first courses I studied to expand my comprehensivism was Giuseppe Mazzotta’s exquisite “ITAL 310: Dante in Translation” from Yale Open Courses. Dante’s La Commedia is, as Mazzotta explains, an encyclopedia of learning making it a mini-course in comprehensivism (read my review of the course). Studying epic poetry redressed a deficiency in my intellectual faculties and opened worlds I didn’t know existed. Alternatively, if you are poetically or spiritually inclined, maybe it is time for some mathematics or hard-nosed engineering? Exploring what is furthest from your current skills and proclivities is, perhaps, the most effective way to rapidly develop your comprehensivism.

Fourth, if my previous suggestions haven’t whetted your appetite, choose one of the universalist traditions. I’d recommend systemics, cultural studies, or synergetics as the most promising, but they all offer some hope of universal applicability. Full disclosure: as Executive Director of the Synergetics Collaborative, my choice of synergetics is clearly biased.

Lastly, if you are not drawn in any particular direction, choose your next comprehensivist exploration at random: there are too many possibilities. There is no right answer. Whatever you explore will bring new magic into your understandings of our worlds and its peoples. Jump in and begin!

Which tradition do you want to explore next? How can our community of collaborating comprehensivists help you get started?

In summary, we have explored the scope of humanity’s great traditions of inquiry and action as four categories: ideas, material culture, social structures, and experience. Then we surveyed those traditions that purport to provide practitioners with a particularly incisive perspective. We ended by offering advice to guide comprehensivists in choosing their next exploration. However, you develop your own personal tradition of exploring and integrating humanity’s traditions, it is certain that the journey will reorganize your mind with new faculties, new meanings, new possibilities, and new adaptability in navigating our always evolving, dynamic civilization.

This essay was written to provide ideas in support of the 29 July 2020 session of “Comprehensivist Wednesdays” at 52 Living Ideas (crossposted at The Greater Philadelphia Thinking Society).

¶ Addendum

The 1h 37m video from the 29 July 2020 event.

¶ The Necessities and Impossibilities of Comprehensivism

04 August 2020 in Resource Center.

If comprehensivism is the process of making sense of it all and of each other, is it even possible? Even if it is impossible, is it necessary that we pursue as many comprehensive comprehensions as we can muster? How can we reconcile the necessities and impossibilities of comprehensivism?

¶ The Necessities of Comprehensivism

Many excellent motivations and reasons for practicing comprehensivism are given in the Collaborating for Comprehensivism site. The inaugural event in the “Comprehensivist Wednesdays” series explored even more (see the video Why be a Comprehensivist?). Angela Cotellessa’s PhD thesis identifies still more.

Here, we will explore three ideas that seem so compelling that we might consider them necessities.

¶ 1. What way or ways of knowing ought a human being practice? What is the proper way of knowing? That is, what approach to learning or epistemology ought we practice?

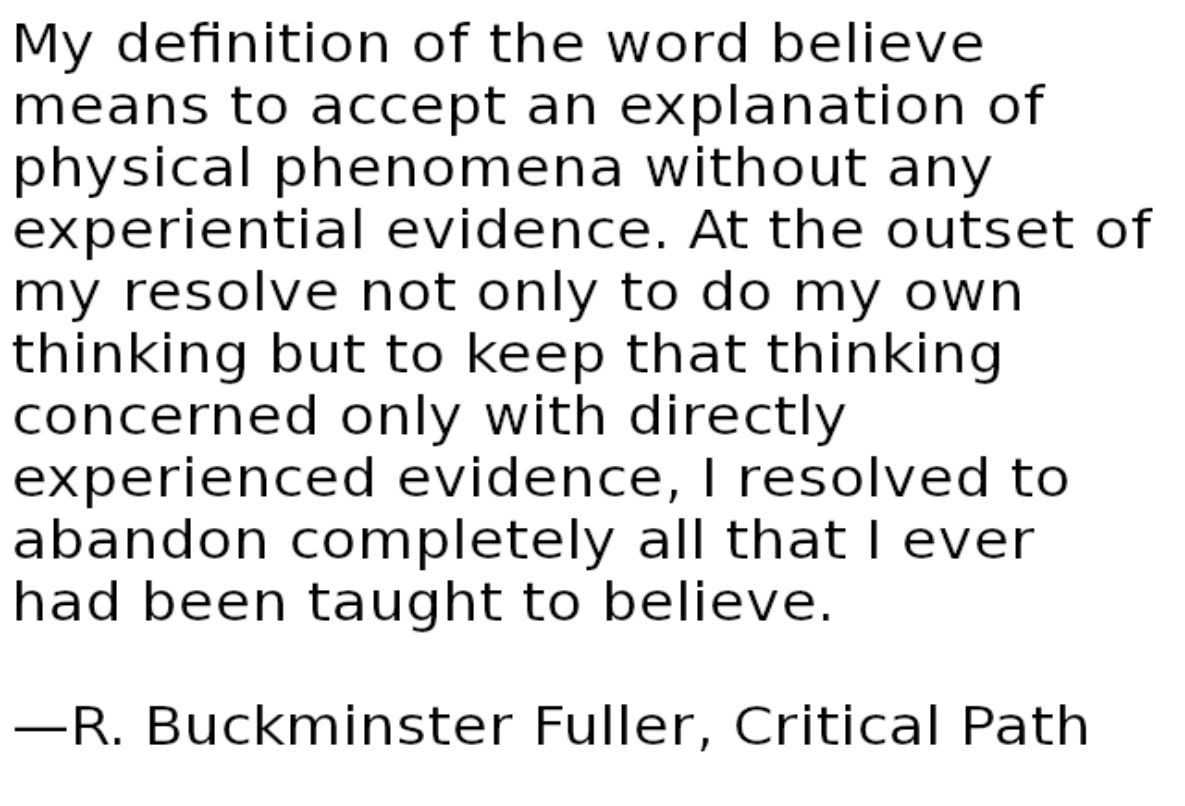

If we start with the plausible assumption thathumanity’s great traditions of inquiry and action encompass all that is humanly knowable, our questions invite us to determine which of the many traditions of inquiry and action might provide the most reliable understandings.

We could speculate; we could guess. We could simply pick the one that we became most enamored with at an impressionable age. Or pick what a teacher, friend or loved one favors. But isn’t that a premature jumping to conclusions?

Instead, we should apply a systematic approach: incrementally explore ever more and more of humanity’s great traditions of inquiry and action. By ever widening our circle of learning, our assessments will gradually become ever more comprehensive. This is the approach of comprehensivity: the state or quality of pursuing comprehensive comprehensions comprehensively.

Each tradition whets its discriminative edge against the others to sharpen and make more robust our own personal, ever-emerging way of knowing, our personal comprehensivity. By integrating more and more wisdom from each thoroughly considered way of knowing, we structure the context and perspective needed to better assess the value of other ways of knowing. By degrees, we organize an ever more refined integrated synthesis. We build what amounts to our understanding of the world and its peoples.

In sum, comprehensivism is a systematic way of learning from our great traditions; it is a systematic approach to knowing or epistemology. If a systematic approach is most proper, then comprehensivism is the proper epistemology, the proper way of knowing and learning. Hence, comprehensivism is a necessity.

¶ 2. What way or ways of acting in the world ought a human being practice? What is the proper way of acting in the world?

To act effectively in the world requires that we understand how the world works well enough that we have some hope that our actions will have our intended effects. That is, proficient acting in the world depends upon our knowing, our learning, our epistemology. Which we just determined is most properly pursued by comprehensivism. So, if effective acting in the world is the most proper, comprehensivism is again a necessity.

¶ 3. Let’s consider this quote from R. Buckminster Fuller’s book Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth:

“We have not been seeing our Spaceship Earth as an integrally designed machine which to be persistently successful must be comprehended and serviced in total”.

Must our world system be “comprehended and serviced in total” in order to successfully provision and steward our global ecosystems, our value systems, our material and energy resources, and our social systems in support of a thriving population of nearly 8 billion crewmates aboard our spaceship and to do so on a regenerative basis for millennia to come?

If humanity does not comprehensively comprehend these world systems adequately to anticipate their possible disruptions and ensure proactive and effective management of the whole world system on an ongoing basis, who will? God? The divine stoic principle of right action in the moment? Luck?

What guarantor for the destiny of Spaceship Earth would you propose?

It could be that comprehensivism collaboratively pursued is the only approach that is systematic enough and thorough enough to offer some hope that we may understand the world well enough to provision a makeshift patchwork that passably supports the ongoing regenerative functioning of the entire world system.

In sum, comprehensivism seems to be a necessity for managing on an ongoing and a regenerative basis the total world system.

¶ The Impossibilities of Comprehensivism

Each of the necessities of comprehensivity indicated above aspires to an ever more comprehensive survey of the full inventory of humanity’s great traditions of inquiry and action. However, it is numerically impossible for any one finite human to thoroughly explore each tradition. Indeed, it is not even possible to list out all traditions available. Hence, each comprehensivist must humbly submit to understanding but a small subset of humanity’s complete cultural heritage.

This is a trivial impossibility for comprehensivism. We should turn our attention to the much more challenging and dangerous pathologies of comprehensivity identified by Harold G. Nelson and Erik Stolterman in their book The Design Way.

-

Analysis Paralysis. When our need and desire for understanding it all results in endlessly gathering more and more information without a means for convergence on an effective way to navigate and manage our initiatives and projects, analysis paralysis is apt to frustrate our objectives. Analyzing all available information seemed to be a requirement for comprehensivism, but it is an impossibility.

-

Value Paralysis. When our need and desire for integrating everyone’s value systems into our comprehensive inquiries and actions without an effective way of transcending their mutual ambiguities and contradictions, value paralysis is apt to frustrate our objectives. Accommodating all value systems in our comprehensive comprehensions seemed to be a requirement for comprehensivism, but it is an impossibility.

-

The Paralysis of Wholism. When our need and desire for integrating the full context of every system we are considering into a Big Picture without an effective means to limit or contain our survey, the paralysis of wholism is apt to frustrate our objectives. Fully assembling our understandings of the world into a whole seemed to be a requirement for comprehensivism, but it is an impossibility.

In considering these impossibilities, we realize that comprehensivism can never be fully achieved; it is an impossibility. Buckminster Fuller also realized this when he wrote in Synergetics “there can be no finality of human comprehension”. So comprehensivism is a guiding ideal; it is an aspiration, not a destination.

¶ Implications for the Practice of Comprehensivity

Buckminster Fuller characterized the plight of comprehensivity with these words, “The more we know, the more mysterious it becomes that we can and do know both aught and naught.” “Aught” means anything and “naught” means nothing. Bucky is saying that we can and do know both anything and nothing.

This paradox that lies at the heart of everyone’s practice of comprehensivism is the creative source of its genius. We can come to know anything! Simultaneously, our profound and inescapable ignorance will forever remain palpable reminding us to stay sober and humble in our assessments.

The necessities of comprehensivity beseech us to practice the art more assiduously. While its impossibilities remind us of the importance of cultivating a humble but incisive judgment, so we can boldly navigate the complexities of our objectives more effectively.

It could be that judgment is the key to an effective practice of comprehensivity.

We need to judge when to diverge and widen our circle of learning and when to converge by honing in on a defined subject until we thoroughly comprehend it. We need to judge when we need to gather more information and when we need to integrate what we have. We need to judge which value systems we can integrate into this project and which to leave aside for the moment. We need to judge if our Big Picture is a good enough whole or if more context is required.

In conclusion, Life is episodic and project-oriented. Our judgment chooses how we furnish each episode, when to put it aside, when to complete it, and when to start the next. Judgment may be all you have to guide you on your path. If you aspire to the necessities of comprehensivism while heeding its impossibilities, your judgment will guide you to your proper way of knowing and doing, to your tradition of comprehensivism. May you judge well and learn enough from each of your inevitable mistakes.

This essay was written to provide ideas in support of the 12 August 2020 session of “Comprehensivist Wednesdays” at 52 Living Ideas (crossposted at The Greater Philadelphia Thinking Society).

¶ Addendum

The 1h 41m video from the 12 August 2020 event:

¶ The Fundamental Role of Story in Our Lives

08 September 2020 in Resource Center

Comprehensivism is the practice of considering with ever-increasing depth and breadth more and more of Humanity’s great traditions of inquiry and action to better comprehend how our worlds work and how they change, so we might all live more effective lives. In this practice, as each explorer reflects on the value of their independent and group learning, they will from time-to-time identify ideas that they think should be collaboratively examined.

Collaborating for Comprehensivism aspires to engage every participant in organizing ideas for the group to explore. We think this kind of engagement of participants is necessary to activate the full potential of the collective intelligence of the group.

To exemplify this aspiration, we will share and explore an idea that we think should be collaboratively examined. Let’s investigate the idea that story may play a fundamental role in all traditions of inquiry and action, in the practices of a comprehensivist, and in our lives.

¶ Is Story Fundamental in Our Lives?

Oral and visual storytelling is known in prehistory. Children love picture books that engage written and visual language. Movies and theater continue to be valued even during global pandemics. We are all moved by good stories. Story is clearly important to our lives, but is it fundamental?

Jacques Hadamard collected evidence that Einstein and others think non-verbally. Mind and thought may extend beyond the reach of story into the realm of the ineffable, beyond what can be described. How might we circumscribe the part of our lives that is about story?

Let’s consider the distinction between what happened and what we say about what happened. The word “fiction” means a construct or invention. What we say about what happened is necessarily an invention of language constructed to report to self or others a story about what happened. That is to say, all description is constructed and invented: it is a fiction.

Story is what is said about what happened, what is happening, or what may happen. All stories are necessarily fictitious even when they adhere closely to the Truth of what happened. In fact, non-fiction is, in a way, more hypocrisy and deception than fiction because it falsely pretends that there is a way of storytelling which somehow provides a privileged access to Truth.

No story, not the most careful scientific report, nor the finest mathematical or logical proof can ever tell us exactly what is, nor exactly what happened. Why? Because, at its best, such reports are symbolic constructs attempting to represent and intimate what is. No description can ever report exactly what happened: that was already lost to the mists of history and the foibles of perception even if your scientific notebook is meticulous!

Arnold Weinstein uses the evocative phrase “fiction of relationship (Weinstein 1981)” to describe both the literature that discusses human relationships (family, friendship, business, romance, and more) and, as Weinstein puts it, “the notion that relationship itself may be a fiction”. We might glean that our stories, (our “fictions”), about relationship are our principal tools for understanding.

It could be that the basic association in a relationship is the fundamental unit of knowing or understanding. Then an algebraic form to characterize a dawning understanding, an apprehension, might be the relationship , meaning is associated with through the relation . Since the relation is a construct, Weinstein’s view that relationship may be fiction seems apropos. Systems of such relationships would form a story. Knowledge seems to be intimately connected to story in this way.

In more human terms, a person is essentially defined by their relationships to place, people, history, values, passions, inquiries, and initiatives. In these terms, Weinstein calls fiction of relationship the “voyage to the other”. In this way, his expression addresses the poignancy of the basic issues of our lives.

In sum, we have a phrase that gets at fundamental aspects of our lives and our basic knowing in the world. The stories we tell are a fiction of relationship. Our lives themselves are a fiction of relationship. Our best languaged way of getting a vague grasp of the wisp of reality is a fiction of relationship.

Let’s take another tack at seeing story’s allegedly fundamental role. If the great traditions of inquiry and action encompass all human knowledge, how does story fit in each tradition?

It is possible to live isolated in the woods and to have great thoughts and build great artifacts, but unless an archeologist discovers your work and manages to piece together enough clues to interpret it astutely, no one will know about it and it cannot contribute to the accumulated wisdom of humanity. Traditions are passed on from person to person. They must be communicated. A tradition necessarily entails communication.

Any way of parsing and communicating experience forms the basis for a tradition. Aggregates of communicated experiences can be organized to form an approach, a way of thinking, a subject, even one’s life’s work. A teacher or their adherents may organize these stories to formally establish a tradition. Of course, any given collection of communicated experiences may dissipate on the scrapheap of yesterday’s babble that didn’t coalesce into something transmitted from person to person.

When our communicated experiences arrange themselves into something that gets passed on, they form the storyline of a tradition. In a very important sense, these stories form the great mythology for each tradition’s cosmogony and cosmology. In this way, story seems fundamental to all traditions of inquiry and action.

In Joshua Landy’s interpretation of Friedrich Nietzsche’s “The Gay Science”, he argues that each of us should “turn our life into a work of art”. Landy adds, “art makes our life beautiful if we tell it as a story”. I hear Landy suggesting that our life should be constructed as an artwork and shared as a self-affirming story. In our language, each life would be presented as a tradition which others may then build upon.

When we tell the story of one of the great traditions of inquiry and action (which might be a story of our own life presented as an artwork) or when we compose a story weaving threads among several traditions, we regenerate Humanity’s cultural heritage, bringing some of that wisdom forward. It could be that story is the warp and woof of the great traditions of inquiry and action, the fundamental structure upon which we build the knowledge of a comprehensivist.

Is story fundamental to our basic understandings? Is story fundamental in our great traditions of inquiry and action and in our comprehensivity, our state or quality of learning that is broad and deep? Is story fundamental in our lives? If so, how so? If not, why not?

¶ What is the Role of Story in Our Lives?

In Dame Marina Warner’s subtle but profound presentation on “The Truth in Stories”, she shows how the fabulist (storytelling) imagination is a form of inquiry. Fantasy, fairy tale, and mythology present, in fact, questions about how things might be, questions about alternative ways of being. Warner says, “The inquiry a story mounts may also take a speculative form: offer a hypothesis, or a set of interlocking and often contradictory hypotheses. This is the enterprise of fantasy.” In Marina Warner’s able mind, the Truth of the fabulist imagination stands next to the methodologies of science as a way of exploring hypotheses!

This might lead us to an important corollary: assertions are a disguised form of question and ought to evoke a state of wondering: Could it be? How might it be? In what situations might it work out that way?

I think Warner’s subtle but penetrating point is that stories always and only present “The Truth” of wondering and inquiry. These Truths of the fabulist imagination may sometimes be more penetrating than what can be disclosed by traditions taking a “neutral” stance including government reporting, journalism, biography, history, and even science.

For our inquiry into the role of story, Marina Warner’s insights suggest to me that the great traditions of inquiry and action and their stories are not imperial impositions for us to adopt like vassals, but instead they are questions that should fill us with wonder: What Truths live here? Which of these wonders might apply in our worlds? How can we make sense of this?

For our comprehensivity, the stories from many traditions of inquiry and action can aid our wondering about the possible ways to organize a human mind and a human life. This archive of wonder and wisdom in the great traditions gives us the tools needed to broaden our understanding of it all. This realization reinforces the insight that comprehensivists ought not dismiss any tradition without wondering about the worlds it might open for our consideration.

(see Marina Warner’s essay “The Truth in Stories”)

To dig deeper, we might look at story through the lens of some theories (which are simply traditions held in high esteem by our culture). Consider Claude Shannon’s 1948 contribution of information theory. It provides a powerful model for communication at a fundamental level. Is a bitstream a story? Yes: at minimum it is the story of getting this message from here to there. But neither Shannon nor his successors in the tradition of information theory have mathematized interpretation. Interpretation is essential to story: both for the teller and the listener. So, we will need a more powerful theory to operationalize story in our lives.

In the theory of symbolic interaction of George Herbert Meade, our minds, our selves, and our behavior are seen as formed by our interpretations of symbols informed by our accumulation of social interactions. Indeed, our thinking and actions are seen as simply the product of our lifetime of evaluated symbolic interactions. Perhaps, we already knew that mind, self, and behavior were all inextricably linked to experience, but symbolic interactionism sees experience as our individually interpreted symbolic interactions situated within our social milieu, our social environment.

For example, in Harvey Molotch’s insightful introduction to the theory of symbolic interaction, the appearance of my neighbor at her doorstep (a symbolic gesture: “I am here”) triggers me to turn my just attempted swat at her friendly, but bothersome dog into a wave, into a greeting. The story shows how our actions are the result of our dynamic interpretation of signs in our social worlds and how we think others will receive our actions.

Signs and symbols stand for other things. Signs include anything we might encounter in our interactions with others including words, phrases, gestures, images, icons, artifacts of material culture, social structures, ideas, and any bundling of experience (whether lived, imagined, or communicated). Symbolic interactionism is the idea that our thinking and acting is a product of our interpretations of these signs and symbols from our social milieu motivated by wanting to form a positive sense of self in the eyes of others, that is, motivated by our sense of dignity.

By emphasizing the interpretative role of the accumulation of our lifetime’s symbolic interactions, the theory gestures to the gulf that separates what happened from our thinking about it. Moreover, each of our interpretations can be seen as a fiction of relationship: we see the fictive role of interpreting symbolic interactions and its role in understanding the world of relationships in which we live.

At a societal level, symbolic interactionism indicates the value of the great traditions of inquiry and action. These traditions are the source of the symbolic meanings intimated in our interactions. Our interpreted interactions regenerate society by rearticulating and reevaluating the traditions that inform each symbolic interaction. As this process permeates each interaction of each person throughout society, the dynamic manifestation in our minds and in our behavior of our reinterpreted and hence reformulated traditions continually regenerates society.

By showing how these interpreted symbolic interactions so directly affect our minds, behavior, and society, the theory makes clear the value of learning from and curating the wisdom in humanity’s vast inventory of traditions of inquiry and action. It provides new insights into how our learning affects us and how that in turn changes the world.

To emphasize this point, it is the stories we tell ourselves and others about the great traditions that informs, and in fact forms, our minds, shapes our behavior, and molds our society. In this sense, these stories directly and profoundly shape the world despite the fact that most of us think changing the world is beyond our control. In fact, each of us changes the world with our every social interaction!

Now we can circumscribe the fundamental role of story in our lives:

-

Story is the fiction of relationship which both forms the basis of our understandings (which are nothing but relationships) and forms the interpretations of our symbolic interactions.

-

Story is the means by which the great traditions of inquiry and action are communicated from person to person and generation to generation.

-

Story is the Truth of inquiry and wonder in our explorations.

-

Story is the dynamic interpretation of meaning in our every symbolic interaction.

-

Story is the way society regenerates itself built on the always reinterpreted and reformulated great traditions of inquiry and action. That is, story is the means through which the world changes.

-

Finally, story is, for all the above reasons, a key tool for the comprehensivist as we strive to make sense of it all and of each other.

Does this circumscribe the fundamental role of story? What are the strengths and weaknesses in this characterization of the role of story? What fundamental role, if any, do you think story provides in our great traditions of inquiry and action, in our comprehensivity, and in our lives?

This essay was written to provide ideas in support of the 16 September 2020 session of “Comprehensivist Wednesdays” at 52 Living Ideas (crossposted at The Greater Philadelphia Thinking Society).

Addendum:

The 1h 33m video from the 16 September 2020 event

¶ The Comprehensive Thinking of R. Buckminster Fuller

07 October 2020 in Resource Center.

Collaborative comprehensivism is participating in groups to incrementally expand the breadth and depth of everyone’s understanding. An effective tool for its practice is exploring ideas from a book. Some participants may be unable to read the book. To provide them with a background and to focus on the key passages to be explored at a particular event, it can be helpful to have a brief for the book. Ideally, the brief will highlight questions to guide and spur a group exploration.

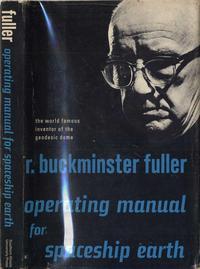

To support book-based events with an example, this resource includes a synopsis of R. Buckminster Fuller’s 1969 book “Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth”. This brief is just one of many possible condensations of the book. It focuses on some of the key ideas that inspired the “Collaborating for Comprehensivism” initiative.

It is common to refer to the author of “Operating Manual” as “Bucky”. To read the book, you can find a copy from a bookseller, or read a 44-page PDF at:

https://designsciencelab.com/resources/OperatingManual_BF.pdf, or read a web-based copy at:

https://web.archive.org/web/20041028062223/http://www.futurehi.net/docs/OperatingManual.html. Below there is a section offering advice for readers of the book.

¶ Comprehensive Thinking

In his 1969 book Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, Bucky Fuller repeatedly surprises us with ways to reimagine our everyday world:

I’ve often heard people say, “I wonder what it would be like to be on board a spaceship, ” and the answer is very simple. What does it feel like? That’s all we have ever experienced. We are all astronauts.

Buckminster Fuller

The fact is we live aboard a planetary vehicle of 6 quadrillion megatons ( kg = lb = megatons) with a 25,000-mile equatorial girth ( km = mi) whose diameter is miles ( km = mi). This tiny bit of agglomerated stardust which we call home is orbiting one of about 1024 stars in the observable physical universe. Three-fourths of Earth’s surface is covered with shallow puddles of water (10,911.4 m = 35,799 ft = 6.78 miles = 0.09% of Earth’s diameter in the Mariana trench) and a thin veneer of atmosphere (100 km = 62 mi = 0.78% of Earth’s diameter to the Kármán line). Our spaceship home is transporting us around the Sun at nearly 70,000 mph (29.78 km/s = 107,200 km/h = 66,600 mph) while rotating on its axis at 1,000 mph (0.4651 km/s = 1674.4 km/h = 1,040.4 mph) while hurtling through space with respect to the cosmic microwave background radiation at nearly 1 million mph (390 km/s = 872,405 mph).

The astronautical is just one of Bucky’s metaphors in a book which entreats us to engage our comprehensivity, our facility for learning that is “macro-comprehensive and micro-incisive” as Bucky puts it. Some readers of “Operating Manual” may get lost in these stories which can be as disorienting as a fairy tale. What are we to make of a work of non-fiction with so many strange stories from such unusual perspectives?

In a previous essay on The Fundamental Role of Story in Our Lives, I emphasized, in following the ideas of Marina Warner, that fairy tales and mythologies are full of the truths of inquiry and wonder. On almost every page during each of my three re-readings of “Operating Manual” over the past year and a quarter, I too got lost in wondering about these stories. What ideas and values are playing out here? In what sense could Bucky be right? In what sense is he mistaken? What is he getting at? Could I make his point better by telling a different story? Bucky writes wonderful literature, but you need to exercise your creative interpretive skills to make sense of it.

In my reading of “Operating Manual” I learned that children have, as Bucky puts it, “spontaneous and comprehensive curiosity”, that Leonardo wasn’t just a polymath but a “comprehensively anticipatory design scientist”, and that over-specialization is the way to extinction and oblivion (Bucky writes, “[S]pecialization precludes comprehensive thinking”). If we dare to listen to the truths and wonders behind Bucky’s mythologizing, we might hear a stern warning about the foolishness of our shortsightedness. Bucky invites us to wonder about the value of a “long distanced … anticipatory strategy” that might be able to see 25 years into the future. He explains the logic governing automation by writing, “automation displaces the automatons.” Automation can free us of drudgery, so we can become comprehensivists.

We also learn from Bucky:

Nothing seems to be more prominent about human life than its wanting to understand all and put everything together.

Buckminster Fuller

This is the creed of the comprehensivist, someone who strives to understand both more extensively and more intensively. It is a basic principle in Bucky’s “Operating Manual”.

The hinge of the book comes in Chapter 4 where we read:

Now there is one outstandingly important fact regarding Spaceship Earth, and that is that no instruction book came with it. … So we were forced, because of a lack of an instruction book, to use our intellect, which is our supreme faculty, to devise scientific experimental procedures and to interpret effectively the significance of the experimental findings.

Buckminster Fuller

The designations “Spaceship Earth” and “instruction book” suggest that our planet is an intricately designed piece of technology. The materialists and atheists among us may be put off by the thought that our planetary vehicle was designed or invented. Religious people may be put off because they may already have studied our “instruction book”. The ecologically or spiritually minded may think its too technocratic.

For reading and interpreting Bucky, we would do better to set aside these intrusive thoughts. Instead, we should attend to Marina Warner’s great insight that mythologies, like Bucky’s, permit us to explore what may be inaccessible to other kinds of writing. How might we interpret Bucky’s mythology of a Spaceship Earth flying a crew of 8 billion humans through space at nearly 1 million miles per hour without an instruction book?

If we had an instruction book, we wouldn’t need to guess at how Nature works. As it is, we have only our intellect and our experience to guide us in figuring out how the world works. Bucky latches on to “generalized principles” such as “the generalized principle of leverage” that we might discover after realizing that the magic log found while stepping on a crisscrossed fallen tree in the woods can be replaced by any pole that can lift any object if there is a convenient pivot point.

Bucky continues,

Only as he learned to generalize fundamental principles of physical universe did man learn to use his intellect effectively.

Buckminster Fuller

A student of David Hume’s great book An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding[6] might object: All we can infer from experience is a “constant conjunction” between an alleged cause and its effect. Our knowledge of “generalized principles” is no more than the custom of repeated attestation creating a confidence in our facts. Hume is correct, there is no principle of reasoning that guarantees the eternal truth of any alleged generalized principle. In fact, history strongly suggests that as our learning becomes ever more sophisticated we will find more and more exceptions and incongruities in our “generalized principles”. But again we should read past these intrusive thoughts to realize that Bucky is getting at a deep truth about our learning: finding abstract patterns that recur repeatedly is a basic part of the knowing of every tradition of inquiry and action, including science.

Bucky invites us to expand our comprehensivity by considering the tradition of general systems theory and asking:

“How big can we think?” …we begin to think of the largest and most comprehensive systems, and try to do so scientifically. … Can we think of and state adequately and incisively, what we mean by universe? For universe is, inferentially, the biggest system.

Buckminster Fuller

Before Bucky defines “Universe”, he scopes its context as “the biggest system”. He is using the word in the sense of the universal set, the set that includes everything that might be considered. Cosmogonists who talk of multiple universes are using the term in the lowercase “u” sense as the speculation that there may be disconnected physical “universes”. I capitalize the “U” in “Universe” because, in the Bucky sense, there can only be one “biggest system”: it is unique; it is a proper noun.

I define universe, including both the physical and metaphysical, as follows: “The universe is the aggregate of all of humanity’s consciously-apprehended and communicated experience with the nonsimultaneous, nonidentical, and only partially overlapping, always complementary, weighable and unweighable, ever omni-transforming, event sequences.”

Buckminster Fuller

Thoughts and ideas and even physical principles such as universal gravitation with its inverse square formula are weightless and Bucky abstracts these to comprise the metaphysical part of Universe. This is a different meaning from the philosopher’s metaphysics as first principles and different from the spiritualist’s metaphysics of a supersensual world. Metaphysics, in the Bucky sense, includes the non-physical, weightless, and ethereal, it includes ideas, theories, descriptions, and principles.

Notice that the center of Bucky’s definition of Universe is “communicated experience”. That is basically what I mean by traditions of inquiry and action which are all about communication from person to person and generation to generation. The crux of Bucky’s Universe is more or less the traditions of inquiry and action which I identified as encompassing the knowing of the comprehensivist. Likewise, Bucky’s Universe encompasses all that we can knowingly talk about.

Bucky’s framing as “Universe” appeals to my mathematical sense: it is all-inclusive but with an experiential focus. The framing as “traditions of inquiry and action” emphasizes the social and historical and so puts experience in its socio-cultural-historical context.

Despite these differences, I claim that these two formulationsBucky’s Universe and Humanity’s great traditions of inquiry and actionare synonymous. Bucky’s concept of Universe as “the aggregate of all of humanity’s consciously-apprehended and communicated experience” scopes the range of all that we can know. Universe is the ken of the comprehensivist. That is exactly the conclusion I reached about Humanity’s traditions. Both Bucky’s Universe and traditions of inquiry and action include all that can be communicated. So, my vision of comprehensivism is, in fact, Bucky’s vision: we just use different framings.

In Bucky’s Comprehensive Thinking, it is recommended that we start our inquiry with Universe, so we do not leave anything out. We then subdivide to isolate the system we want to consider.

A system subdivides universe into all the universe outside the system (macrocosm) and all the rest of the universe which is inside the system (microcosm) with the exception of the minor fraction of universe which constitutes the system itself.

Buckminster Fuller

It may take many subdivisions, as in the game of 20 questions, to identify the subsystem with which we are concerned. One benefit of this approach is that the full context is included in our inquiry itself. This is Bucky’s approach of Comprehensive Thinking.

Other traditions of inquiry and action may use other ways to pursue their inquiry. To be broadly comprehensive, we ought to consider and assess these other approaches too. But here our aim is to summarize Bucky’s approach as presented in Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth: systems thinking starts with Universe and divides into the subsystems of relevance for this inquiry.

From this introduction, what do you think of the Comprehensive Thinking of R. Buckminster Fuller? What are the strengths of this kind of thinking? What are its weaknesses or deficiencies?

¶ Regenerative Evolution of Spaceship Earth

Another important feature of Bucky’s Comprehensive Thinking is his nuanced approach to synergy:

Synergy is the only word in our language that means behavior of whole systems unpredicted by the separately observed behaviors of any of the system’s separate parts or any subassembly of the system’s parts. There is nothing in the chemistry of a toenail that predicts the existence of a human being.

Buckminster Fuller

Bucky suggests that synergy is inherent in all systems. This principle of omnipresent synergy justifies starting with the Universe and subdividing: otherwise we risk overlooking the synergetic effects that are part of the context, part of the larger wholes, but invisible within each subsystem. I think it is this feature of the principle of synergy that makes the following Bucky assertion so penetrating:

“We have not been seeing our Spaceship Earth as an integrally designed machine which to be persistently successful must be comprehended and serviced in total.”

Buckminster Fuller

Another reason for managing the Earth system comprehensively is the dynamical nature of Bucky’s definition of Universe. Recall that the subject of our communicated experiences is “nonsimultaneous, nonidentical, and only partially overlapping, always complementary, weighable and unweighable, ever omni-transforming, event sequences”. The Universe is, as Bucky puts it, “an evolutionary-process scenario”. As such, Bucky’s phrase “inexorable evolution” is the design process of Universe unfolding to form the events of our experience in perpetuity. This further supports the idea that to successfully manage the omni-transforming scenarios of Spaceship Earth, we must comprehend and service the total Earth system synergetically.

Bucky’s system of Comprehensive Thinking includes general systems theory with its topologies of interrelationships and its geodesics or minimal energy pathways. This is a powerful conceptual toolkit. Applying it to the understanding and servicing of our spaceship, we realize that since Earth’s resources are unevenly distributed, a global industrial system as “a world-around-energy-networked complex of tools” had to be invented to give Humanity the ability to take care of the vast and vital metabolic needs of Spaceship Earth and its crew.

In Bucky’s vision, as stewards of our Spaceship Earth, we have a primary function to organize our know-how and know-what to operate our spaceship as an ongoing regenerative evolutionary process. This kind of Comprehensive Thinking is needed to comprehend and service our spaceship in total. We may even begin to see our planetary function as a “metabolic regeneration organism” as Bucky puts it. The “regenerative landscape” of future possibilities awaits our design attention to imagine and create our regenerative evolutionary future.

What do you think of Bucky’s way of connecting his Comprehensive Thinking to the regenerative metabolic futures of Spaceship Earth? What are the merits of this approach? What are its deficiencies?

¶ Comprehensivism: Putting Bucky’s Comprehensive Thinking in Context

Among the many reasons I wrote the above brief for Bucky’s “Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth” was to complete a four-part introduction to my vision for comprehensivism, the practice of the art of ever broadening and deepening our understanding of it all. The impetus for this introduction to comprehensivism has been the opportunity to organize topics for Comprehensivist Wednesdays.

In this essay, I connected Bucky’s Comprehensive Thinking with comprehensivism. I linked Bucky’s notion of Universe to Humanity’s great traditions of inquiry and action. Bucky’s Comprehensive Thinking and his notion of regenerative evolution, which I consider to be the interlinked dual theses of “Operating Manual”, comprise what I called The Necessities of Comprehensivism. Although Bucky may have appreciated what that essay calls the impossibilities of comprehensivism, to my knowledge, he never distinguished those concerns. My characterization of the fundamental role of story in our lives was my attempt to capture the role of story as the central “communicated experience” in Bucky’s definition of Universe and in the traditions of inquiry and action. That essay also helped me explain the value of the mythologizing in Bucky’s “Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth”.

The integrated significance of these four essays is to show how my vision of comprehensivism is the identification and abstracting of a significant piece of Bucky’s system of comprehensive thinking as documented in Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth”. Specifically, I pulled out Bucky’s word “comprehensivity” and turned it into collaborative comprehensivism, a group learning initiative.

There are a few differences between my vision and Bucky’s. I think we should consider all of Humanity’s traditions of inquiry and action and not insist, pedantically, as Bucky sometimes did, that we must always start with Universe and subdivide. I think exploring other traditions and other approaches to inquiry ought to be part of collaborative comprehensivism.